Games were always monetized. So why do gamers hate that word, and what’s the right approach?

Attract Mode

If any component of game making could use a snappy demo to entice gamers, it is surely monetization. Gamers typically associate the word with things they don’t like: those underhanded, distasteful tactics in games aimed at parting a fool and his money. To them, the people that ‘do monetization’ see players as potential ‘whales.’ They jam ads, in-app purchases, and other self-serving features into the game. In too many gamer’s eyes, they use all their psychological and data analytic tricks to get players to keep playing and keep spending, with good gameplay taking a backseat to profits.

On the other side of the fence, monetization is just a fancy word for the mechanisms, however roundabout, by which game developers get paid for doing their jobs. If you develop games for your livelihood, those games need to make money. Ergo, most games must be monetized.

I am both a gamer and a developer, so I had to reconcile these two conflicting viewpoints. Though business is not my primary field, I still needed the gamer and the developer in me to be at peace with any approach to monetization I used: to feel their concerns were satisfied. Perhaps you’re in the same position. If so, join me on a trek through the different ages of monetization, finding the keys to defeating the evil boss and reaching the happy ending.

Well, yes, if all goes well. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves…

Level 0: Tutorial

We begin our journey in the relative safety of Level 0, by asking a naïve question.

Q: Why do we developers monetize games?

A: To make money!

Or to put it more altruistically, we want people to give our company money, so that we can keep making games. The way we can do that in a market economy is by offering things consumers consider valuable, and are willing to pay us to have or use. If the consumer doesn’t perceive anything of value in what we offer, they won’t pay for it, and we fail.

We make a game valuable in many ways:

- allowing the player to do things that are engaging, interesting, and challenging.

- including content with intrinsic value like art, story, and music.

- providing an experience that’s fun, unique, and novel.

Other forms of media, like films or comic books, can be valuable for many of these same reasons. Though we most frequently hear about monetization in the narrow context of free-to-play mobile games, any game – indeed, any thing – that has ever made money was by definition monetized, regardless of its platform or business model. Monetizing a game may look different from monetizing other things, but monetization itself is not a new idea.

Level 1: Simpler Times

Since monetization is not new, let’s explore Level 1: the way things were first sold.

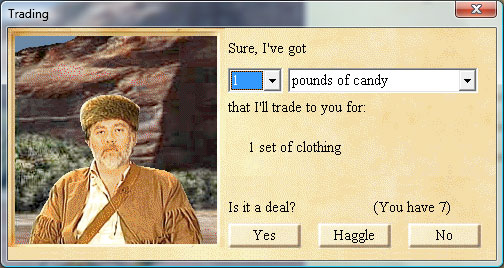

Oregon Trail II (1995). As in, when you bought games on CD’s. Not

as in, when you had to barter supplies with the closest fur trader.

Traditionally, we offer a game you can play once you buy it. Everyone understands this business model, because it’s how we buy cans of soup and new shoes and most any everyday, non-digital product. Make a game good enough to be worth buying, market it well, and profit!

At least, that’s half the battle. We want them to play the game, too! Even if playtime had no bearing on a game’s financial success, we developers, as people who take pride in our work, would still naturally want people to play it. And they’ll only play the game if they see something of value in playing it. This is the first key to monetization: the value-to-play.

When people can’t play your game until they pay for it, it’s easy to think of getting them to buy it and getting them to play it as the same objective. But this distinction becomes important later. If the player doesn’t see the value in playing the game, they won’t. Even a free game can be not worth playing, so all games must have a value-to-play.

Level 2: But Wait, There’s More!

Level 2 presents a new environment: games that make revenue beyond their initial purchase price. For a long time now, gamers have had the option to play more than the base game they initially encounter. Early 90’s games like id’s Wolfenstein 3D and Doom were released in episodes as shareware. Titles like these proved that a game that was free to play, with the option of paying for more content, could be successful.

As storage media improved, more content with higher quality could be packed onto disks. Franchises like The Sims made much of their revenue through expansion packs, which had the advantage of not requiring development of a whole new game. As internet access and download speeds improved, these were supplanted by downloadable content, which doesn’t carry with it the cost of distributing physical media.

Same tune, different instruments: episodic shareware via mail order, expansion pack via DVD, and downloadable content via Steam.

Though these three forms of additional content have evolved with the times, they all provide content that is analogous to the content in the base game. It’s more of the same kinds of things: a new batch of levels, a new weapon, new character customization choices, etc. So just as the base game can be valuable – through the experience it provides, the art and music it incorporates, and all those other things mentioned above – these forms of additional content can be valuable for the same reasons.

This is important for achieving the second key of monetization: the value-to-pay. For games to make revenue beyond their initial purchase price, they must offer something of additional value the player could be willing to pay for to have. The games here on Level 2 need to present this value-to-pay in addition to, but separate from, the value-to-play. If players don’t perceive your additional content as having value, no one will buy it.

Level 3: Obey. Conform. Consume.

As we leave Level 2, we find ourselves once again in new territory: the realm of today’s free-to-play games. Some mobile titles are like we’ve encountered before: they offer a free version that serves as a demo, and a premium version that unlocks the rest of the game. But far more popular, and much more lucrative in this space are consumable virtual goods. People pay real money to ‘buy’ more 💰 (currency), ⚡️ (energy), and/or ❤️ (lives). The player spends or expends these limited resources, and then they are gone.

For developers, consumables remove the last barrier to unlimited revenue potential. A pack of DLC levels is great, but that content still takes time and money to create. Here on Level 3, players can buy and re-buy those same 💰, ⚡️, and ❤️ symbols over and over again. When everyone who wants your DLC has bought it, you stop making money. But consumables can generate revenue as long as players are consuming them.

Consumables are profoundly powerful. They are like spirits: intangible entities that can cross the threshold from the virtual, incorporeal realm of in-game economies into the physical realm of actual dollars and cents. That makes developers the mediums, with the power to channel these spirits. We have a duty to use this power responsibly.

If that’s a bit too New Age for you, let me describe their power a different way. A video arcade owner has some control over how much play his customers get out of a handful of quarters. Similarly, a mobile developer can adjust the ‘exchange rate’ of how many gold coins a player gets for their 99¢ in-app purchase. Both are limited by what the market will bear. But the arcade owner must factor in the cost of powering and maintaining his machines, while the mobile developer has no such concerns since gold coins cost nothing to produce.

So are these ghostly, consumable microtransactions bad? Are they the evil boss we are here to vanquish? Close. Consumables tend to serve another master, and that’s the one we’re after. Often hidden under multiple, exchangeable in-game currencies, consumables are typically designed as the solution to a problem that, from the perspective of good gameplay, doesn’t need to exist. These games have artificial limits or gates on how much or how often you can play. Speed bumps, if you will.

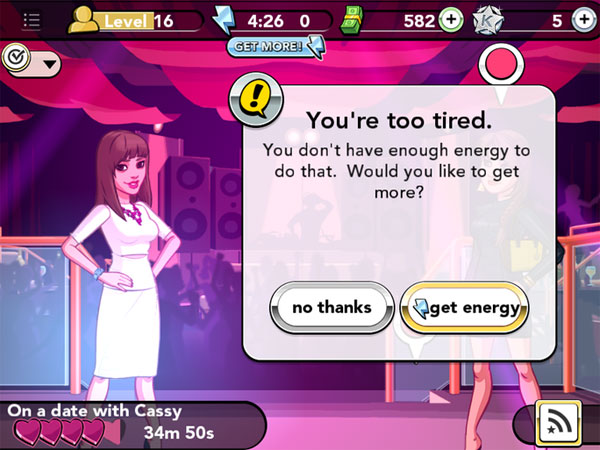

For every 💰, ⚡️, or ❤️ in a game, there is a corresponding system which must be fed these items to keep playing at ‘full speed.’ And when progress is tied to how many consumables a player buys instead of their performance, we call this pay-to-win. Gamers get out the torches and pitchforks when they see pay-to-win, especially in games with player-versus-player competition.

What are you, my Mom?

Boss Level: The Pay-to-Win Speed Bump

While I use the term “evil boss” tongue-in-cheek, I still choose it deliberately. These ‘speed bump’ systems are objectionable in part because they are artificial constructs. The developer goes out of its way to add them. One might argue the same is true of everything else in the game. So why do gamers accept, say, a system in an RPG where mana potions are a limited resource, but not a system in a free-to-play game where lives are a limited resource?

First, because most elements of a game, from the overarching story to the tiniest visual effect, are motivated by making a good game. Gamers can recognize that the mana potions are there for the sake of game balance, and level progression. Speed bumps are motivated by something else – monetization – and that’s enough to raise eyebrows. Without the speed bumps in place, the game may not succeed financially. But without the mana potions in place, the game may not succeed as a game, which is what matters to a gamer.

Second is the deceptiveness of layers of abstraction, which try to mask what is otherwise an acute application of the principle that time is money. For every shiny “suitcase of bills,” there are expensive items that would take a hundred hours of playtime to buy with currency amassed through gameplay alone. The express purpose of these speed bumps is to impede the player’s progress and fun: to restrict the gameplay to the point that, hopefully, those 💰, ⚡️, and ❤️ look valuable enough to buy.

Yet as a designer, insuring a game isn’t ‘too fun’ strikes me as a backwards concept, akin to a grocery store worrying if their free samples are ‘too delicious.’

But don’t give him the good stuff, or we’re ruined!

After battling through all these previous levels, how do we defeat the evil Speed Bump boss? Like any good boss fight, it is through the application of what we’ve learned in previous levels. Do consumable virtual goods fit with the earlier concepts of value-to-play and value-to-pay? If a player pays for them, do they receive additional value?

At best, it’s hard to make that case. The player can progress faster, and play longer or more frequently by buying consumables. Their value is that they counteract the speed bumps… which were added so players would have something to counter.

If the boss in our monetization game had an introductory cutscene, he would sound like this:

Gamer: I’m trying your game and I like it. I’m having a fun time!

Speed Bump Boss: You’ve had enough fun. Pay me $0.99 or stop having fun now.

Level 2 was more agreeable, wasn’t it? Not because expansion packs or shareware are superior, but because the approach was friendlier:

Gamer: I’m trying your game and I like it. I’m having a fun time!

Level 2 Character: Great! Would you like to have even more fun for $0.99?

Gamer: Okay!

Whether a particular monetization tactic is seen as ‘fair’ or ‘evil’ depends largely on the developer’s approach. If you come at it with the goal of getting the player to buy stuff in your game, you’ll focus too much on ‘closing the sale’ and too little on the means you’re using to accomplish that end. Don’t set out to create more annoyances until the player submits and gives you money.

This guy. Don’t be this guy.

Instead, come at it with the goal of adding value-to-pay: offering things valuable enough that some players want to buy them. Consumers will appreciate a game that’s designed first to be a fun game, and if it could be more fun with an in-game purchase, that’s okay too.

Bonus Level: Ads

While I’ve dedicated most of this article to microtransactions, I’d be remiss to not mention in-game advertising. Unlike microtransactions, ads can usually be added a la carte: they don’t need to be tightly integrated into a game’s economy, for example. Still, there are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ ad implementations, and what separates one from the other is the same principle we found with consumables.

On one hand, you have games that put up a 15 or 30 second video ad after your character dies. These games are basically using ads punitively: you have to watch the ad as a penalty for losing, before you can play any more. They impede the player’s ability to play the game as much as he or she wants, and the advertisers probably don’t appreciate their wares being presented as obstacles, either.

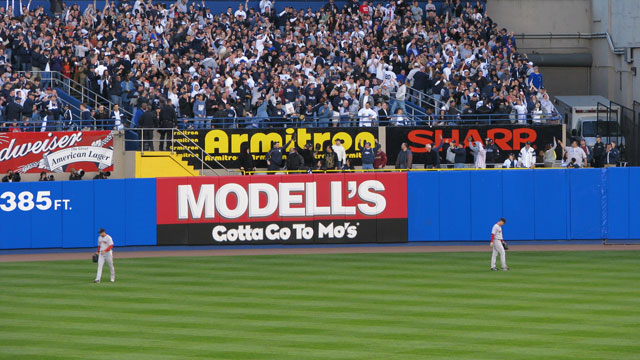

Then there are games with more passive ads. A portion of the screen is reserved for an endless slideshow of banners that plays during some or all parts of gameplay. If the player is lucky, the ads aren’t too intrusive to distract from gameplay, and if the developer is lucky, some players are actually interested enough to tap on them. This is akin to in-stadium advertising: players would prefer to skip it, but at least it doesn’t interfere with the game.

Up next, apparently: the Arizona Armitrons versus the St. Louis Sharps.

The third type of advertising isn’t negative or even neutral, but actually positive. These games give the player the option of watching an ad, with the promise of an in-game reward, like 100 gold coins. A short-sighted developer too concerned with getting as much ad money as possible will likely overlook this option. But it gives the player a much appreciated flexibility: sometimes I want those 💰, while other times I just want to keep playing. And since the incentive is a virtual good, it costs the developer nothing. The size of the reward is only dictated by game balance. Finally, since anybody can watch an ad regardless of their ability to pay, it’s also a way to counteract pay-to-win.

Final Cutscene

- Players don’t like speed bumps that impede their progress.

- Let non-payers have a good time.

- If your game has microtransactions, it must offer value-to-play and value-to-pay to be successful.